https://mailchi.mp/tintypegallery/httpswwwtintypegallerycomexhibitionsdread-one-day-at-a-time-951370

Archives

(Addison J. and Kidd N. 2019) Co-authored chapter for upcoming publication: Campbell L. Ed. Leap into Action: Critical Performative Pedagogies in Art & Design Education. Peter Lang USA.

Regulation, Resistance, Readiness and Care: What can be learnt by performing the peripheral behaviours of artists?

(Addison J. and Kidd N. 2017) Co-authored chapter :Turvey, L and Walton, A Eds. In Site of Conversation: On learning with Art, Audiences and Artists. Tate Publishing:

https://www.tate.org.uk/about-us/projects/in-site-of-conversation

https://www.tate.org.uk/research/research-centres/tate-research-centre-learning/in-site-conversation-films-papers

Live Resource

Learning it

by Andrew Marsh

Five Years

2007

Tricks in the Art of Doing

I was going to write something clever. A classy piece of short fiction with a contextualisation of Jo Addison’s work woven into it. A story that would mimic the interweaving of Suburban romanticism and its seedy underbelly that runs through her work. Something quintessentially English. Something involving blocks of flats, service stations, Ford Mondeos, and community centres.

The problem with this, I realised, is that I would not do the work justice this way. It wouldn’t fit. Mainly because it is all there in the work, and the narratives evoked are far more intricate and alluring than my short fiction could ever be. Now, of course, I am faced with writing about the work, or should I say the ethos of the work, as to describe the work in this space would be akin to writing the fiction/contextualisation piece.

The main thing that has always struck me about Jo Addison is that she does not approach her subject matter from any high ground. In fact her work rejoices in the quotidian idiosyncrasies that surround us, and more often than not the beauty of these brief encounters with the world pass us by. The poignancy of two derelict petrol stations opposite each other on a no longer frequently used stretch of road. The small but perfectly, and elegantly, hand written phrase‘Fuck off you’ on the stairwell of a block of flats. These are the things that Addison presents to us to be celebrated. The triumph of individuality in an otherwise regulated suburban society. Marc Augé calls it ‘tricks in the art of doing’. The point at which we assert some type of intervention into an otherwise mundane process – be that conveyer belt work or day-to-day living.

Of course, not all of Addison’s subjects are consciously making interventions into otherwise workaday existences, Addison then plays the role of tour guide in order that we see the humour and elegance in the miss-spelt, the crossed out, the improvised, or handmade.

Underlying this celebration, however, there is an inherent seediness. A certain frisson of the threat of something unsavoury just around the corner. Addison’s postcard sized paintings of brake lights in the distance or little chef signs are like Caspar David Friedrichs for the service station generation, but exactly what will take place in that car park when those brake lights turn left is entirely up to you. It is at this point that the unknown event is simultaneously romantic and yet just a little bit unwholesome. It is the feeling you get in a cul-de-sac of semis with pristine lawns and cleaned cars. The feeling that you would really rather not know what goes on behind those regularly washed net curtains.

This juxtaposition of celebration, humour, and the unsavoury is what makes the work so enchanting, and my initial grand intentions so impossible. So, no fictitious texts here, just a short take on the work of Jo Addison, and trust me it really is for the best because if you give it chance her work will change the way you see, and think about, the everyday world that surrounds you.

Andrew Marsh, curator and writer based in London

Visitors

Outpost

2007

Upon entering, the viewer first encounters a multifaceted grey rock-form crouching before a differingly scaled picnicing cave recessed into the OUTPOST wall. A perfect cardboard sheet stained with a black patch and tiny lighting, and a wall mounted semi-circular night scene with supermarket signage completes the room.

Interview between Jo Addison and Lawrence Bradby, November 2007

Lawrence Bradby: Most of your pieces are quite small Jo, but they exert their influence over far more of the gallery than the bit they actually occupy. Could you describe how that works?

Jo Addison: Each piece is an extract from a larger place. First you see them from a distance, and then you have to travel across the space towards them for the details to become clear. I like to think that once you get there they render your body a bit clumsy. It becomes cumbersome in relation to them – just a mechanism for getting you there and holding your head and eyes in the right place.

LB: So, if I’ve understood it right, you see the miniaturised scale the scale makes you feel uneasy, not quite at home in yourself. what do you think makes your pieces unsettling?

JA: The things you’ve mentioned are faithful, detailed replicas of the original. In contrast, I’ve given spare attention to detail and used materials economically. The workings are exposed and parts of the objects are incomplete. They’re not absolute, precise descriptions but indications of places that are at once inviting and indifferent, intimate and generic. If I were to describe such places through more faithful modelling of finer materials there would be less room to recall your own encounters with them.

LB: Two of your pieces in the show use small light bulbs surrounded by an area of black paint. For me the surrounding blackness suggests that I’ve glimpsed one of these ‘intimate and generic’ places in passing, in the night, out of the window of a train or a car. Or that the spreading blackness is a shared cultural memory where these generic places are stored.

JA: Yes, I like the way you’ve described it as a sort of bank of those memories. The blackness is metaphorical and physical: a very immediate, almost childish description of night and the way it deletes other features.

JA: Yes, I like the way you’ve described it as a sort of bank of those memories. The blackness is metaphorical and physical: a very immediate, almost childish description of night and the way it deletes other features.

LB: Like the barn you mean, because I still can’t see it.

JA: ‘The most photographed barn in America’ features in Don DeLillo’s White Noise. The building is caught in a kind of loop – the naming of it prescribes one’s experience of it, which, in turn, enhances its name. Similarly, the places I’ve described are designed and named so as to be experienced in a very particular way. They’re not always encountered as ‘real’ places but unspectacular stops along the way.

No One Sees The Barn

2 to 21 November 200710b Wensum Street

Tombland

Norwich

Norfolk

NR3 1HR

Englandquestions@norwichoutpost.org

www.norwichoutpost.org

Telephone +44 (0) 1603 612 428

No One Sees The Barn

Outpost

2007

Preview: Thursday 1 November 2007, 6 – 9pm

On view: 2 – 21 November 2007

12noon to 6pm daily

OUTPOST is pleased to present new work by Jo Addison.

Addison will show several small sculptures, which will be installed within the exhibition space. In most cases the work will be supported by the walls of the gallery – a minimally engineered arm holds a work out from the periphery of the space – another sculpture is embedded in the paint, plaster and wood that covers the gallery masonry. The work occupies these spaces in front and behind walls with modesty; any figuration is deliberately slight and the closest we get to showmanship within this body of work are flashing LEDs imitating distant lights at night and a whirring re-cycled motor which turns a rickety turntable. In the case of the latter, the movement is important: in association with a miniature cardboard totem stuck to the turntable top, it signifies a roadside moving past us.

Reflecting on the turntable piece entitled “Services” one is aware of Addison’s experimentation with what we might call positive and negative images and their relation. A cardboard turntable is transformed into a desolate landscape or perhaps we should say an empty landscape. How do you show the landscape that surrounds a motorway at night – a scene which yields no information bar the colours and blurring semiotics of signposts as they pass in the periphery of the car’s headlights? The artist provides a response; a visibly empty scene is substitute for the invisibility of the countryside at night. The movement, the signpost and the lack of anything else is the working of this piece.

Information comes to us sparingly in all the works intended for exhibition. Addison expresses something uncanny about the appearance of a supermarket sign over a nocturnal tree line. Although it is man made; pertaining to be civilised, it is not so much comforting as it is foreboding. The sign marks a supermarket complex; possibly a retail park, the type of site along with service stations and picnic clearings that can be found dotted along stretches of countryside that follow motorways and A-roads. On these sites locality means very little: we shop/rest/dine amongst unfamiliar faces in an unfamiliar place, which is made to seem familiar. These points of respite on a long journey appear in the distance, for example over treetops. However they are the not the destinations we aim for, often just single manned, 24hr outposts that we trade with through a letter box sized opening in a window.

Jo Addison lives and works in London. She studied at the Slade School of Fine Art and NSAD. She is currently a visiting lecturer at the University of the Arts London, Kingston University and RCA.

For more information please contact Lawrence Leaman – lawrence@norwichoutpost.org or on 07817 743969

OUTPOST/10b Wensum Street/Norwich/NR3 1HR

Tel: +44 (0) 1603 612428

questions@norwichoutpost.org

www.norwichoutpost.org

No One Sees The Barn

by Ben Roberts

Five Years, London

2009

Preview: Friday 31 January 2009, 6 – 9pm

On view: 31 January – 15 February 2009

In the 2002 John W Walter documentary How to Draw a Bunny Ray Johnson talks about an element within his own practice he refers to as ‘moticos’. Johnson likens these small packets of collages, photos and found material to the flashing glimpses between the cars of a passing freight train: a moment in which the majority of our vision is temporarily obscured, save for a tantalising sliver of detail at the edge of the image. He claimed they were everywhere in our daily life; all we needed to do was learn to see them and we’d be richer for it. It’s a suggestion which also rings true when looking at the work of Jo Addison and Alice Walton.

Walton’s collages and drawings are similarly concerned with the nature of how we see and assess the images around us. That Walton originally took as source material pages rent from jazz mags, and that she continually seeks to erase the female form, suggests a politicisation in the work. However, latterly she has primarily been using pages culled from second-hand art history books that often feature women. These figures are then crudely obscured using tape or paint, leaving only the surrounding architecture of the original visible. It would be all too easy to claim this for a feminist revision of the misogyny of art history, or of visual culture more generally, but that would also be misleading. The work takes a broader view. In her sculptures, too, the use of materials, siphoned from the world around and manipulated to new and sometimes obscure ends, is key. Walton’s method of construction through simple acts of appropriation directly asks the viewer to question the nature of what they are seeing: how the image is constructed, not in a literal fashion but in terms of the content. It is a simple yet very effective device to overtly obscure an image whose internal mechanics and structure may appear familiar yet, in doing so, not present a political dialogue but rather an experiment in visual language. Walton separates the process of looking from understanding and lays them side by side, yet what you see and what you get will very much depend on you.

The evocative image of the cityscape glimpsed between the edges of the train carriages has a cinematic resonance within the context of Addison’s sculptural constructions. The pared-back, muted tones of the work, its reduced and apparent physical simplicity, suggest an empty banality. But these are objects as mediums, single frames of film that describe the entire scene. Continually reworked and simplified to their core, Addison’s sculptures come to represent a universality of experience of time and place. They are everywhere and nowhere, her greys are those of the multi-storey car park and the motorway junction roundabout at 3am. Her’s is the furniture dumped in the brambles at the edge of the park. Yet despite their aspirations to universality these objects command a very personal response. The tension at the centre of the work is the conflict between the very personal response to the evocative object and the often universal nature of those non specific, momentary experiences of time and place. Addison’s constructions are the starting points for an internal journey in which the object may be long forgotten before we realise where we’ve gone.

The emotional and intellectual preconceptions we bring, as viewers, to the work of both these artists will determine our visceral response to them. In different ways they both require an assessment of our reactions and assumptions about them by asking how we got there in the first place. Often, however, this is not explicit and can only really be understood by looking at the edges to grasp what we’re seeing right in front of us.

Ben Roberts is Programme Co-ordinator at Camden Arts Centre and Dean of Brown Mountain College of the Performing Arts.

FIVE YEARS Unit 66 6thfloor, Regent Studios, 8 Andrews Road, London E8 4QN

info@fiveyears.org.uk

Gallery Open Sat-Sun 1-6pm

That was a good day

Herbert Read Gallery UCA

2009

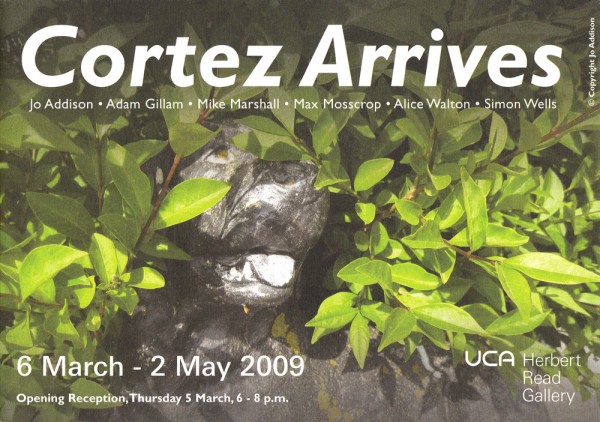

Jo Addison

Adam Gillam

Mike Marshall

Max Mosscrop

Alice Walton

Simon Wells

Preview: Thursday 6 March 2009, 6 – 8pm

On view: 6 March – 2 May 2009

Photo by Jo Addison

Snow Falls Upwards

by Kate Fowle

Staring out of a window on the 29th floor I’m watching snow fall upwards. A few blocks away cranes are lifting an airplane out of the Hudson River. Struck by birds, the 500,000 pounds of US Airways flight 1549 fell out of the sky shortly after take off, but everyone was saved and the pilot is a hero. Now, cradled in mid air, the bulk looks strangely animate, giving off the nobility of a stranded whale. Meanwhile the radio is announcing that tomorrow a new era dawns as Barack Obama becomes President of the United States.

It’s not only Cortez who is in strange territory…

Cortez arrives at an unknown shore

he is absolutely lost

and he is enraptured

They are one of twenty-six fragments written by the poet and activist George Oppen (1908-1984) that were found scrawled on envelopes and scraps of paper in his study after his death. Its uncertain if it is complete but it doesn’t really matter. They arouse the promise of wonder as they are.

Last Saturday I went to a talk by two neurologists. Towards the end they were asked if there is a difference between the mind and the brain. The answer got complicated, but in short they said that when something is “right”, the body gives off a physical response—goose bumps, palpitations, sweaty palms, dilated pupils—before the mind “knows” as much. The gap between the responses of the body and the mind is a matter of milliseconds. That’s nothing. But then again it’s everything because if knowing can be physically manifested, even just in the form of a momentary disorientation, then it follows that art could be understood as the response to discerning the difference between the mind and the brain in relation to stimuli.

This is different to the ensuing academic debate about the production of art as a form of knowledge, which prioritizes the cognitive value of art. It’s also not about art practice as research that produces knowledge, or artifacts as embodiments of knowledge. While all such incarnations of course exist, and the discussion provides some kind of credible and logical accountability for art practice, it removes space for the type of art that resists meaning as knowledge, or which is produced as a visceral response to “knowing” something.

All the artists in Cortez arrives deal with this conundrum. They eschew the notion that art needs to “represent” or to “signify,” instead producing works that end up being “of themselves.”

They share an instinct to synthesize material processes and imaginative expression, developing visual languages that personify the subtleties and contradictions of experience. They accumulate, filter, speculate on, and play with ideas, embracing the absurdities that may spring forth from daily life. Relishing the intrinsic foolishness of experimental creation, they want to find forms that make sense of phenomena. Working across drawing, painting, sculpture, collage, video, sound, and film, what unites the artists’ divergent styles and techniques is the resonance of process. You can sense their engagement with materials is directly related to their obsession with digesting what they encounter, read, watch, hear, and think.

Interaction with their artworks stirs a response akin to the sensation of watching a good dance performance, wherein you become aware of what it feels like to have a body. This way of knowing something isn’t just contained in the head, where trains of thought are sparked and memories evoked, but reverberates through one’s whole being. The kind of recognition that is triggered cannot easily be identified because it is mental and physical at the same time. In a similar way the works in Cortez arrives are less explicitly communicative than experiential, embodying the open-endedness of potential.

Kate Fowle is a curator and writer based in New York.

Herbert Read Gallery University for the Creative Arts, New Dover Road, Canterbury, Kent CT1 3AN

www.ucreative.ac.uk/galleries

www.cortezarrives.com

Cortez Arrives

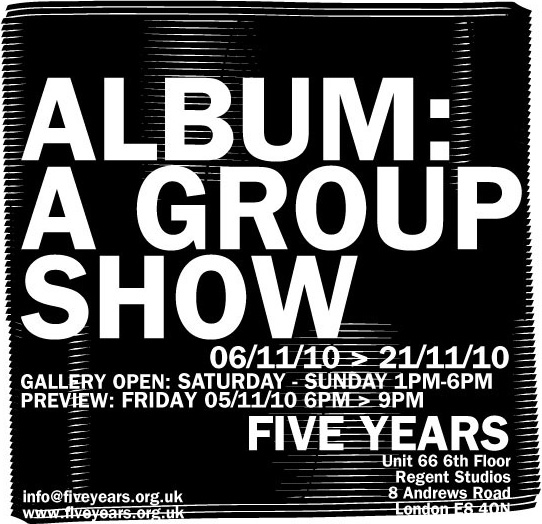

Five Years

2010

Jo Addison

Emma Hart

Anna Lucas

Louisa Martin

Alice Walton

Maria Zahle

Curated by Leanne Turvey

Preview: Friday 5 November 2010, 6 – 9pm

On view: 6 November – 21 November 2010

Gallery Open: Saturday > Sunday 1pm – 6pm

In December 1987, one week prior to its release, all 500,000 copies of what became known as the Black Album were destroyed. Prince had reconsidered his project, cancelled it and recalled all pressed copies. When Warner Bros released the album in 1994 Prince’s spokesperson quoted him as saying ‘the contribution I want to make doesn’t sound like that.’ (1994, St Paul Pioneer Press).

Album has been put together through a series of conversations with the contributing artists about the processes and decisions they use to define when something they have made or done becomes an artwork.

Some of the ideas that became interesting were to do with being able to situate an exhibition earlier in the process of making work. Could an exhibition become somewhere that organizes a discussion between a developing work and the artist? If exhibitions operate as a way of defining an artists’ practice by the work that is selected, how could an exhibition deal with those remainders of an artist’s practice which hover between the studio and the gallery? To what extent would artists take a risk with this? After all, the Black Album was one of Prince’s most critically acclaimed albums so could an exhibition be a space to share work that sits outside the work normally seen?

For most of the artists this issue of the decisions involved in realizing art work was interesting enough. To some extent what ever is happening, and for whatever reason, the exhibition remains the same – a place for exposing a practice that for a large amount of the time remains unseen.

FIVE YEARS Unit 66 6thfloor, Regent Studios, 8 Andrews Road, London E8 4QN

www.fiveyears.org.uk

Album: A Group Show

Notes on the object as thing | James Böhm | 2012

Does Jo Addison’s work allude to objects or restage what essentially an object is – a thing? What kind of encounter is staged? What are we actually looking at, or wanting to hold or touch? We encounter them as objects by of way of their ‘thingliness’. What is this thing state? Are we on unfamiliar registers?

A thing has two common trajectories: Expansive – the thing is the essence of the object, once all conceptual schema has been transcended we arrive at the substance of the object; the Thing which holds all properties together; the Thing-for-itself, it’s own cause, outside of the objective connectedness of things; the unknowable Real Thing. Reductive – reduced to a thing; a thing and nothing more; no use value and hence no value for us; that it is just something at all; the Mere Thing.

There is a language of thinghood subsisting and repressed in objects evoked in Addison’s work as much as the language of objects, objects known and to know. In this sense, her objects feel familiar and right.

Why do they feel right? Is this working at the level of intuition? But these objects are activated conceptually – as though they could have, should have , have had or will have a character of purpose. These are defamiliarized everyday objects rather than abstractions of objects. They persist in their specific objecthood – yet without the register of objectivity; of use value, function, causality, etc. A rightness that appeals less to a language of unconscious archetypes than to the everyday encounter with things. Things to pick up, to support, to look at. That this thing should be here and not there. But to find determinations for why, without the language of function – hence, the aesthetic decision of it will look good here; it feels right etc., misses their specific language as a thing: the language which shadows and evades instrumentalized identity. Because every object is also a thing.

This thingliness then, is it merely in a mimetic relation to objects? It’s like an object but it isn’t; it’s like a feeling of an object; it’s like an abstraction; it looks purposeful, etc. We can never say what it is only that it isn’t quite what it looks like. But these are less a parody of objects in general than a specific object displaced. A thing is the most general property of all, yet Addison’s objects resist the generic by being too singular in their construction: their quality of being made – with intention.

Neither entirely abstract nor generic and neither entirely a mimetic shorthand of objects. Yet the thing-object relation persists. A Thing recalling a distant objecthood? (a fragment, a memory) or projecting a proto-objectivity? (a model) In both, the encounter with the thing is subordinated to either a past or future idea-object. But these are present things that aren’t awaiting an objective form. These things are from the present world, of the stuff of things in general and things in themselves, acting upon us and prompting our actions, of what we use, hold, pick up, open, close, find beautiful, find funny etc…..This familiar world is disclosed when objects have been quietly obscured.

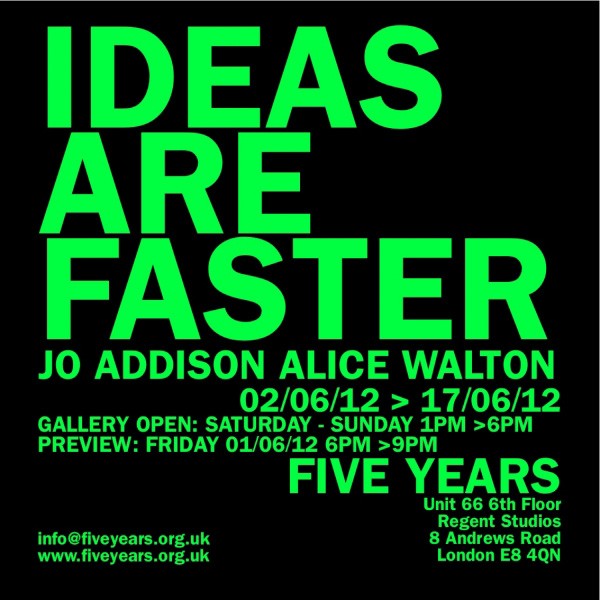

Ideas are faster

Garageland review of Jo Addison exhibition Not Trees and People at Tintype, 2013

Not Trees and People

Five Years

2012

Jo Addison

Alice Walton

Talking of the speed and mass dissemination of art through books in the late 1960s, Seth Siegelaub described ideas as being ‘faster than tedious objects’. Here, by contrast, Jo Addison and Alice Walton present unashamedly slow, obtuse objects.

Addison interprets mundane objects and images with loose figuration and a deliberately provisional approach to materials. Things are depicted by implication and reduction, rather than by detailed description.

‘Does Jo Addison’s work allude to objects or restage what essentially an object is – a thing? What kind of encounter is staged? What are we actually looking at, or wanting to hold or touch? We encounter them as objects by of way of their ‘thingliness’. What is this thing state? Are we on unfamiliar registers?’

Walton’s sculptural objects are configured to support and re-present collections of found images. Constructed from everyday materials such as cardboard, Polystyrene or plasterboard, the elements are simply assembled with the method of production left clearly visible.

‘There is a surface that you can’t see through, laid over with a cut surface you can see into. A mirror not reflecting back, but drawing in. It is active in transforming – just as the opacity is active in muting, ignoring. And there is an underneath. These surfaces play with our activity of looking’.

FIVE YEARS Unit 66 6thfloor, Regent Studios, 8 Andrews Road, London E8 4QN

www.fiveyears.org.uk